Sfinge ‘e San Giuseppe

So, yesterday (March 19th) was San Giuseppe (St. Joseph’s Day) which is kinda like Italian Father’s Day. It’s really convenient with Mothering Sunday falling on the following weekend.

Anyways, as a treat, after an excellent dinner of Pasta e Ceci (which is what’s traditional) my wife decided to make Sfinge ‘e San Giuseppe (also known as “Saint Joseph’s Donuts” or “Saint Joseph’s Cream Puffs” – pronounced /’ʃfɪnd͡ʒ(ə)/ in Napuletano). All they are are choux pastry puffs filled with sweetened ricotta, or mascarpone – both of which are usually flavored with citrus zest – or cannoli cream, topped with a cherry – sometimes with a dusting of ground pistachio. There’s also a zeppule variant in which the pastry part is deep fried, rather than baked.

They were magnificent. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

Era De Maggio

Meaning “It Was of May” in Napuletano – Both the lyrics were written by Salvatore Di Giacomo and the music composed by Mario Costa in 1885. My favorite recording of it was by Roberto Murolo some time in the 1950s:

With the fact that the Coronavirus may keep us stuck isolated until May, it seems far too appropriate.

Era De Maggio

in Neapolitan

Viersetto 1

Era de maggio e te cadeano ‘nzino

a schiocche a schiocche li ccerase rosse,

fresca era ll’aria e tutto lu ciardino

addurava de rrose a ciente passe.

Era de maggio; io, no, nun mme ne scordo,

na canzona cantàvemo a ddoje vvoce;

cchiù tiempo passa e cchiù mme n’allicordo,

fresca era ll’aria e la canzona doce.

E diceva: «Core, core!

core mio, luntano vaje;

tu me lasse e io conto ll’ore,

chi sà quanno turnarraje!»

Rispunneva io: «Turnarraggio

quanno tornano li rrose,

si stu sciore torna a maggio,

pure a maggio io stonco ccà».

Viersetto 2

E sò turnato, e mò, comm’a na vota,

cantammo ‘nzieme la canzona antica;

passa lu tiempo e lu munno s’avota,

ma ammore vero, no, nun vota vico.

De te, bellezza mia, mm’annammuraje,

si t’allicuorde, ‘nnanze a la funtana:

ll’acqua llà dinto nun se secca maje,

ferita d’ammore nun se sana.

Nun se sana; ca sanata

si se fosse, gioia mia,

‘mmiezo a st’aria ‘mbarzamata

a guardarte io nun starria!

E te dico: «Core, core!

core mio, turnato io sò,

torna a maggio e torna ammore,

fà de me chello che vuò!».

It Was of May

my English translation

Verse 1

It was of May, and they were falling into your lap

bunches and bunches of red cherries,

Fresh was the air and all of the garden

was scented with rose, for a hundred paces.

It was of May; I, no, I don’t forget

a song sung with two voices;

more time passes and more I remember

fresh was the air and the sweet song.

And she said: “Love, love!

my love, you’re going far away;

you’re leaving me and I count the hours,

who knows when you shall return!”

I responded: “I will return

when the roses return,

if this bloom returns in May,

then in May I will be here.”

Verse 2

And I returned, and now, like that time,

we sing together the old song;

time passes and the world turns,

but true love, no, that doesn’t change course.

Of you, my beauty, I fell in love,

if you remember, in front of the fountain:

The water there inside never dries,

and a wound of love never heals.

It never heals; that healed

if it could be, my joy,

amidst this perfumed air

I would not be looking at you!

And I say to you: “Love, love!

my love, returned I have,

May returns and love returns,

do with me what you wish!”

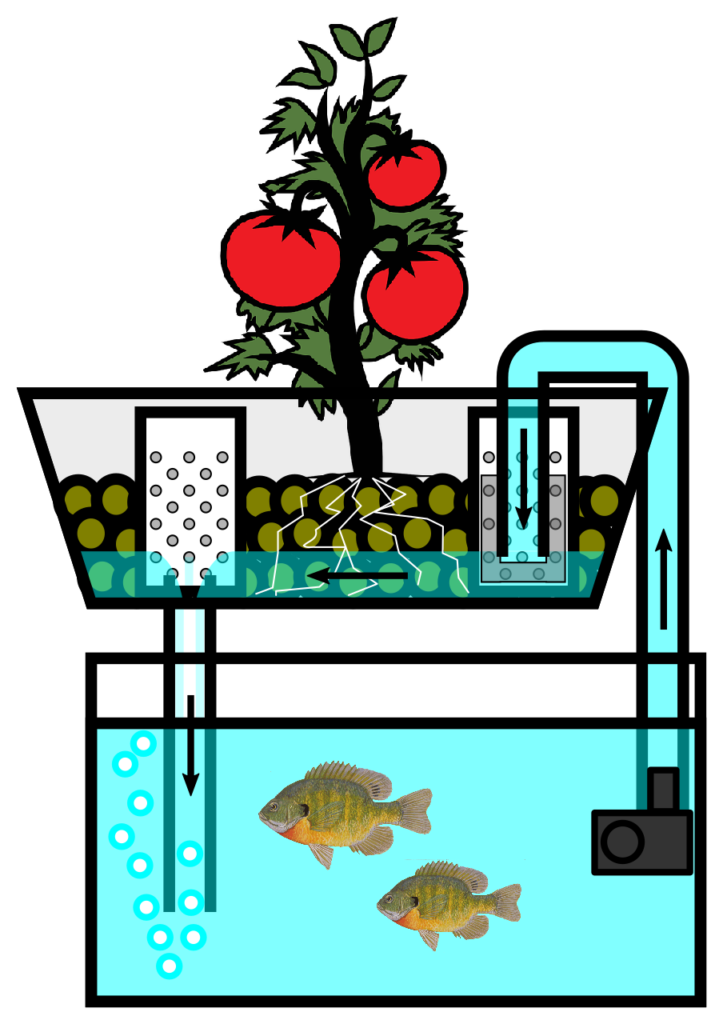

Aquaponics

So everyone knows that I keep native (and naturalized) fish. In my collection I have various sunfish (bluegill, pumpkinseed, etc.), mummichogs, bullheads, shiners, creek chubs, mirror carp, and even a brace of goldfish (those laste two were a failed science experiment… but now beloved pets).

The wonderful thing about natives in NJ is that you don’t need to worry about heating your tanks (they’re comfy with the local weather), and that they all are quite happy in sub-optimal water conditions (they don’t mind low to even moderate levels of pollutants, they’re happy in virtually every pH a human wouldn’t mind swimming in, and some could care less about salinity etc.)

However, like all fish, they like to produce a lot of waste – in the form of ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4+). In order to handle that waste, every aquarist needs to cultivate a colony of two different types of bacteria in the tank’s filter, gravel, and other surfaces that break the ammonia down. The first type of bacteria (nitrosomonas) break those compounds down into nitrite (NO2-) which is less poisonous that ammonia. The second type (nitrospira) take the nitrites and break them down into nitrate (NO3-). Like with humans, nitrate isn’t poisonous to fish, unless it’s in seriously high quantities.

Once the colonies of bacteria keeping this nitrogen cycle in check are large enough that there is virtually no ammonia or nitrite detectable in the water (i.e. they eat them as fast as its produced and ultimately turn them into nitrate) the tank is considered “in cycle,” and the major maintenance at that point is to do regular, weekly water changes to remove the excess nitrates – which are simply waste, and clean out the filter and gravel (where the bacteria grow) from residue.

However, there are plenty of other living things out there that absolutely love to eat nitrates, specifically plants: Especially big leafy greens, tomatoes, and other vine fruit.

This is where aquaponics comes in. Like with hydroponics where the plants are grown in gravel or other media with flowing water to deliver the nutrients, instead of using commercial hydroponics solutions, I’m able to use the water from my aquaria to grow vegetables and fruit. Tank water simply contains (nearly) everything your average garden needs to grow already in it, and the plants that feed off of it remove (nearly) all of the waste that conventional water changes and filter cleanings do.

It’s a serious win-win. 🙂

My Prototype Rig

Now, with aquaponics, like with hydroponics, there are dozens of methods to choose from, and lots of highly opinionated people out there about what works best. My goal in putting together my prototype was to see how well a proof of concept system would work, made from a bunch of materials that I simply had lying around my house. To that end, based on the drawing above I put together:

- A 10 gallon tank (filled with young pumpkinseed sunfish and its own conventional tank filter – the water and nutrients).

- A 16 quart Steralite plastic container (the grow bed).

- A bunch of quartz aquarium pea gravel (the growing medium).

- A drain pan coupling, drilled in and sealed to the bottom of the Steralite container with a rubber washer.

- A few lengths of PVC pipe, one for the input, and one for the gravel guard output with holes drilled in them at regular intervals.

- A pump to circulate the water (I had a spare canister filter I used).

- Some filter pad or filter floss for the input (to strain out any solid waste).

- A 90 watt equivalency LED spotlight (which pulled ~10 watts), eventually upgrading to two 120 watt equivalent bulbs (each pulling ~12 watts).

In the end, the prototype looked like this:

The Prototype, implemented

The pumpkinseeds (and a few mosquitofish).

The initial planting of seedlings: Tomatoes, basil, oregano, and an avocado (that later didn’t make it).

The canister filter pumped the water up into the grow bed, where it flowed over to the gravel guard on the output, and flowed back down into the tank, both cleaning and aerating the water at the same time. I had to re-house the basil and oregano, because the tomatoes quickly dominated:

And just today, I had the first blossoms open:

The Second Rig

The month after I started the Prototype, I decided to break down my 40 gallon tank rack, and convert the top two tiers of space into a single grow bed shelf.

Putting two 40 gallon tanks on the bottom rack (our wild specimens on the left, out domesticated sunfish on the right), I invested in some Hefty 40 quart storage tubs (two per tank), plumbed them, filled them with gravel, and bought some dedicated Beckett 290 gallon per hour pumps to keep the water flowing. For lighting, I put two of the 90 watt replacement full spectrum LED lights hanging above each tub.

One of the four 40 liter tubs.

The injection mold point is precisely the right size for the plumbing.

I drilled it out, cut it, and shaved it.

The coupling and washer installed. This allows for a 1in PVC return pipe.

The first two tubs plumbed with gravel guard (2 inch PVC) installed. The left one running.

Having 1″ PVC returns at a length of approximately 2 feet allowed the returns to act like trompes, pulling air back down into the tanks, so when they run I don’t need to use an air pump to power a bubbler. 🙂

On the input end, I had to build a PVC splitting pipe for each tank, so that the water coming up from the pump watered both tubs evenly. I figured out a way to rig up some smaller CPVC in a “u-bend” so that the water also pushes air into the water before it hits the gravel bed as well – so there’s oxygen introduced on the way in, and oxygen introduced on the way out.

Once I had all four beds set up, I planted them one by one and watched things grow.

In the beds we planted – from left to right (1-4):

- Two kinds of heirloom tomatoes.

- Strawberries in the front, basil in the middle, oregano in the back.

- Strawberries in the front, kale in the middle, blueberries in the back.

- Bibb lettuce all throughout.

So far, only the basil has come ripe enough for us to enjoy on two occasions in caprese. It has the crisp bite of spinach and a really deep flavor.

That’s it for now. In my next entry I’ll go over some of the pitfalls I came across, as well as the next phase of this project’s prototype. 🙂

Peace

-Steve

Coronavirus

Looks like the Caruso Family is going to be sheltering in place for a while due to the outbreak. Raritan Valley is extending Spring Break by an additional week, and during that time we Faculty are getting ready to teach classes online until April 10th.

As a result, to prevent going slightly mad, I’m going to be working on (well, continuing to work on) a number of projects in between recording lectures and grading. On the docket for future posts here include:

- My growing aquaponics rig, and plans underway for building additional rigs out on our porch, and on top of the bumpout/den.

- DEGAS 2.0 – Which I’m implementing in PixiJS with WebWorkers.

- All of my new art I’m painting with DEGAS will be – appropriately – posted on my Art Blog.

- Translations of various works in Neapolitan I’ve been messing about with.

- Any fishing I manage to get done, if any (in remote areas where there are no other people around).

Stay tuned.

Peace,

-Steve

Napuletano Preposition/Article Combinations

I’ve been compiling these from the songs and classical poetry I’ve been reading lately, and I figure that they should be put all in one place for reference.

The most used prepositions in turn-of-the-century Napuletano (Neapolitan, or Southern Italian) are:

| Napuletano | Italian | Meaning & Notes: |

|---|---|---|

| d’ / ‘e | di | “of”, d’ in front of vowels, ‘e everywhere else. |

| a | a | “to,” triggers doubling of the next consonant. |

| da / ‘a | da | “from”, often just as da |

| ‘n | in | “in,” usually prefixed on the word it precedes (e.g. ‘nciello). |

| ncoppo | su | “on” |

These combine with the definite articles:

- ‘o – masculine

- ‘a – feminine

- ‘e – plural

- ll’ – preceding a vowel

And these combinations are are completely different from Standard Italian:

| ‘o | ‘a | ‘e | ll’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sing. | pl. | ||||

| d’/’e | d”o | d”a | d”e | ‘e ll’ | (same as sing.) |

| a | ô | â | ê | a ll’ | (same as sing.) |

| da/’a | da ‘o | da ‘a | da ‘e | ‘a ll’ | (same as sing.) |

| ‘n | dint”o | dint”a | dint”e | dint’all’ | dint’ali’ |

| ncoppo | ncopp”o | ncopp”a | ncopp”e | ncopp’all’ | ncopp’ali’ |

For da/’a, very often (especially in older Napuletano) it will provoke the article to keep its l (e.g. da lo, da la, da le, da ll’).

Other prepositions in Napuletano follow similar patterns too, such as pe, nfino, etc. and I’ll update this article here with more later.

6lb Common Carp Catch

So back on Tuesday, my sister Liz was over and feeling down so I said, “What the hell, let’s go fishing!” so we went to Johnson Park – my usual spot for bluegill. It was cold, the fish weren’t biting. After about an hour – and trying nearly every lure in my box and a quarter loaf of bread – we had plenty of nibbles, but only caught one 3-4″ gill. It was a bit disheartening.

On the side I decided to bait a hook with a bread ball and throw on a large 1/4″ splitshot and let it sink to the bottom, hoping to go after a bigger bluegill. A couple casts and drops didn’t pull anything up, and in the normal way of things, I forgot about the rod.

Fast forward about 10 minutes: We get our second fish: Another puny 3-4″ bluegill, and before we’re able to get him off the hook and toss him back, we hear the drag on the forgotten rod start to squeal, and the rod start to work its way over the dock’s rail.

Something big was on it.

We strung the small gill up above the water and I grabbed the rod before we lost it and started reeling in… and if you were there you probably heard a panicked exchange somewhere along the lines of:

“Get the net!”

“Where’s the net?”

“In the cart!”

“I don’t see a net!”

“It’s the collapsed thingy!”

“The collapsed thingy?!”

“Take the rod!”

“Got it!”

“Don’t let it get away!”

“I’m trying!!”

“I’ve got the net!”

“Get it over here!”

“I’m trying!”

“Switch!”

“Get it! Get it! Get it!”

etc.. 🙂

It kept pulling on the drag and trying to go under the dock, but by some miracle (the fish was 6 pounds – and the line was 4 pound test, and it fought the whole damn way) we managed to net it and bring it up onto the dock. It was too big for the bucket, and at nearly 23″ it was by far the largest freshwater fish either of us had ever caught.

It was a freaking Pokémon.

Peace,

-Steve

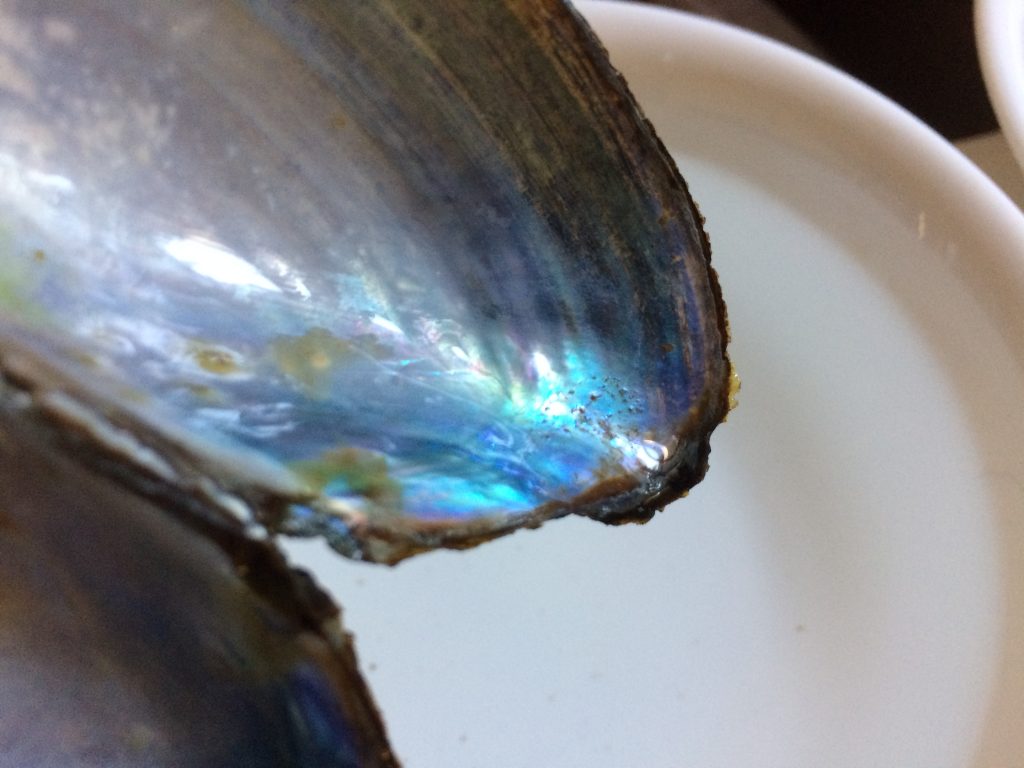

Freshwater Mussels

Most people don’t realize it, but New Jersey is the home of roughly two dozen freshwater mussel species. These aren’t the blue or green marine muscles you’re probably most familiar with over pasta with garlic and butter. These are their freshwater cousins, the bivalves that live in brooks and streams throughout the State.

What makes them so special? Well first, they are the filters of our rivers and streams. They eat small particulates, plankton, and algae from the waterways and are amazingly efficient at it. A few of these mussels can clear out a 5 gallon tank of water in a matter of hours that would otherwise be too murky to see through. They are also important food for birds and mammals. As a result, healthy populations of freshwater mussels indicate a healthy waterway.

Secondly, their lifecycle is fascinating. Some species can live for decades, where others for up to a century – which is a lot longer than their marine cousins. Unlike other bivalves like clams, they have distinct sexes, and when they release their larvae (called “glochidia”) in order to survive they need to attach themselves to the gills or body of a host fish for several weeks and feed off of them. Some species’ females actually deploy lures – which are parts of their bodies which they puppeteer – that look like the natural prey of their hosts. When the fish dive in to attack, they’re sprayed all over with larvae, which heightens the chance that some will latch on.

Third, they are capable of making things of beauty: Freshwater pearls. In fact, the largest American freshwater pearl on record was found right here in New Jersey. As the story goes, in the 1850s, a man by the name of Daniel Howell apparently sat down to a meal of freshwater mussels that his wife had prepared for him, and bit down on a 400 grain (~130 carat) freshwater pearl – something about the size of a golfball.

Where the details of the story get a bit squiffy, there does appear to be a core of truth to it. My wife (whose hobby is genealogy) on a lark, managed to track down Daniel Howell’s household, to find that in 1860, he and his wife had a boarder by the name of John McCaucklin who was a bridge tender for the Raritan Canal. The likely scenario is that McCaucklin brought some mussels he cleaned out of a canal lock home for dinner, and that’s when the discovery was made.

Sadly, after being cooked the pearl’s luster would certainly have been destroyed. However, a few years after the Howell Pearl was found (circa 1857), a man by the name of Jacob Quackenbush over near Patterson discovered a “perfectly round, pink pearl” that was 93 grains (~30 carats) in size. Nicknamed the “Patterson Pearl” or the “Queen Pearl” it was sold to Tiffany Co. for $1,500 (roughly $50,000 modern money) who then flipped it to a French jeweler for $2,500 (roughly $80,000 today) who then sold it to Empress Eugenie de Montijo, the Queen consort of Emperor Napoleon III.

Once gain, where the core story is true, the details proved a little squiffy. It is believed that this pearl now resides in the Royal Ontario Museum as part of a snake-headed brooch; however, that pearl is not round, nor pink – it is a silvery baroque-style (“crinkly”) pearl – but its weight matches precisely.

These pearl finds caused a “pearl rush” or “pearl mania” in the later half of the 1800s which began to deplete mussel populations. It got worse between 1890 and 1930, because freshwater mussel shells – specifically the mother-of-pearl interiors – became the most popular and common source of buttons in North America, prized for their carve-ability and opalescent sheen.

It was only until the advent of commercial plastics that the button industry collapsed, and a hundred years later, mussel populations have built back up once more. Freshwater mussels once again represent the largest portion of biomass in many waterways throughout the State, and are pretty much off the radar of the average New Jerseyian.

So, should you drop whatever you’re doing and run out to the nearest stream or river to look for pearls because now it’s “safe”?

Well, no. There are still serious caveats and considerations.

Like I mentioned at the beginning – where are some dozen+ species native to New Jersey, all but three of them are severely endangered, and are protected at either the State or Federal level. The three least concern species are the:

- Eastern Elliptio (Elliptio complanata), the

- Alewife Floater (Utterbackiana implicata, formerly Anodonta implicata), and the

- Eastern Floater (Pyganodon cataracta).

There are also several introduced or invasive species that are “safe” (or “compulsory” to remove in the latter case) which include the

- Paper Pondshell (Utterbackia imbecillis – what a binomial name – it almost looks like it means “say again, idiot?” – however “utterbackia” means “outer-round” or “outer-pearl” and “imbecillis” means “fragile” – an apt description of this species’ ultra-thin shell), the

- Lilliput (Toxolasma parvum – introduced in a few places in South Jersey), the

- Chinese Pond Mussel (Sianodonta woodiana – highly invasive, apparently piggybacking in on tilapia gills), and the

- Giant Floater (Anodonta grandis – a close relation of the Eastern Floater) apparently introduced in the State, whose status has not been assessed.

Everything else is on the “do not touch” list (or rather, catch and release immediately).

Only a small portion of these protections are a holdover from “pearl/button mania” as some species in some places simply evaporated and could not be replaced. The biggest contributing factor, however, is habitat depletion: Dams, serious pollution, and the death or depletion of host fish (some mussel species are very specific about their hosts, and if those disappear, so do the mussels). Invasive species like Asian clams (Corbicula fulminea) are also competing for food and space, too. So, if you’re caught keeping even the shell of one of the protected species (and you can’t prove you’ve collected them from a jurisdiction that they are not protected) you’ll be hit with a serious fine, and have all of your fishing equipment confiscated.

What makes it harder is that some of the endangered species can be confused with the common species, so you’ll need to be familiar enough with these critters in order to tell them apart safely.

What makes it even harder (and ironic) is that most of the State-sponsored identification keys require you to observe internal features of the shell… in other words a dead specimen (so, yes, it’s pretty much, “these are protected so don’t kill them or else, but you can’t tell if it’s protected for certain until after you kill it…” – although if you’ve found an empty shell, these features are convenient to use).

Even if you’re good with your identification, there are limits on harvesting. Since all freshwater mussels are classified as Non-Game Species, you must get a special scientific collection permit which is a separate thing from the normal freshwater fishing license, or the saltwater registry. If you don’t have it, you’re in serious hot water and additional trouble.

So what can one do to appreciate these fascinating critters without trouble? There are two things you can do. First, you can take part in a local Mussel Survey. There is an ongoing effort in the Delaware Estuary. But one can always survey an area unofficially using the Delaware Estuary’s protocol and submit their findings of any endangered mussels (or other endangered animals) directly to the State.

Second, thanks to local muskrat and raccoon populations, collecting the shells is incredibly easy – they tend to leave little piles of them occasionally on the shores. Some of them are rather large and can contain beautiful blister pearls that can be made into jewelry.

Over the course of the next month, I’m going to try and share pictures of my own shell specimens, as well as my progress in several freshwater mussel projects and research I’m fiddling around with, so stick around. It’s bound to be interesting. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

Quick Update

As I’m taking an extended Facebook break (no worries! no one caused it; I’m simply taking the research about social media and happiness to heart 🙂 ) I have decided that I will take up personal blogging again here and there. Since this blog syndicates everything I write directly to Facebook, all of my Facebook friends will be able to keep up with what I’m doing, too – and if anyone wants to comment, they’ll have to do so here.

And I’m doing quite a bit! I’ll go into more detail in subsequent posts, but in no particular order I am:

- Finishing up my SIGGRAPH’18 poster on DEGAS before the conference, itself, in August.

- Synthesizing rubies and sapphires in my basement using 1850s-era technology.

- Trying to grow opal from waterglass and dirt.

- Hunting for freshwater mussels in the Raritan River and its tributaries.

Stay tuned. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

DEGAS Before And After Example

My lovely wife. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve