Most people don’t realize it, but New Jersey is the home of roughly two dozen freshwater mussel species. These aren’t the blue or green marine muscles you’re probably most familiar with over pasta with garlic and butter. These are their freshwater cousins, the bivalves that live in brooks and streams throughout the State.

What makes them so special? Well first, they are the filters of our rivers and streams. They eat small particulates, plankton, and algae from the waterways and are amazingly efficient at it. A few of these mussels can clear out a 5 gallon tank of water in a matter of hours that would otherwise be too murky to see through. They are also important food for birds and mammals. As a result, healthy populations of freshwater mussels indicate a healthy waterway.

Secondly, their lifecycle is fascinating. Some species can live for decades, where others for up to a century – which is a lot longer than their marine cousins. Unlike other bivalves like clams, they have distinct sexes, and when they release their larvae (called “glochidia”) in order to survive they need to attach themselves to the gills or body of a host fish for several weeks and feed off of them. Some species’ females actually deploy lures – which are parts of their bodies which they puppeteer – that look like the natural prey of their hosts. When the fish dive in to attack, they’re sprayed all over with larvae, which heightens the chance that some will latch on.

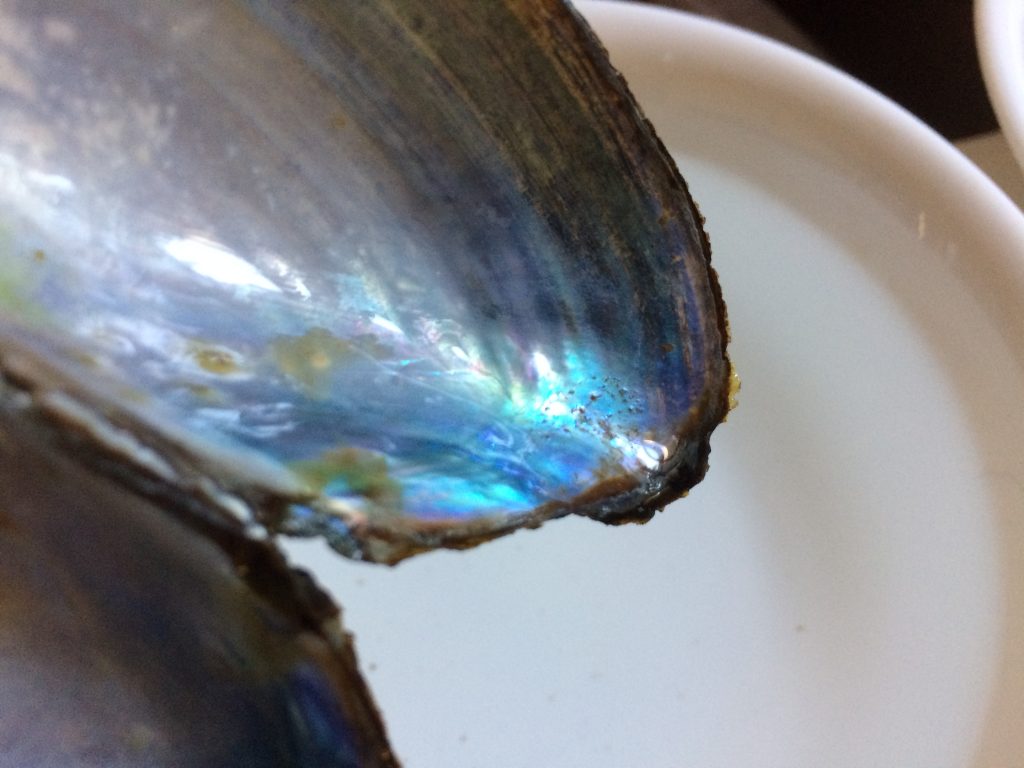

Third, they are capable of making things of beauty: Freshwater pearls. In fact, the largest American freshwater pearl on record was found right here in New Jersey. As the story goes, in the 1850s, a man by the name of Daniel Howell apparently sat down to a meal of freshwater mussels that his wife had prepared for him, and bit down on a 400 grain (~130 carat) freshwater pearl – something about the size of a golfball.

Where the details of the story get a bit squiffy, there does appear to be a core of truth to it. My wife (whose hobby is genealogy) on a lark, managed to track down Daniel Howell’s household, to find that in 1860, he and his wife had a boarder by the name of John McCaucklin who was a bridge tender for the Raritan Canal. The likely scenario is that McCaucklin brought some mussels he cleaned out of a canal lock home for dinner, and that’s when the discovery was made.

Sadly, after being cooked the pearl’s luster would certainly have been destroyed. However, a few years after the Howell Pearl was found (circa 1857), a man by the name of Jacob Quackenbush over near Patterson discovered a “perfectly round, pink pearl” that was 93 grains (~30 carats) in size. Nicknamed the “Patterson Pearl” or the “Queen Pearl” it was sold to Tiffany Co. for $1,500 (roughly $50,000 modern money) who then flipped it to a French jeweler for $2,500 (roughly $80,000 today) who then sold it to Empress Eugenie de Montijo, the Queen consort of Emperor Napoleon III.

Once gain, where the core story is true, the details proved a little squiffy. It is believed that this pearl now resides in the Royal Ontario Museum as part of a snake-headed brooch; however, that pearl is not round, nor pink – it is a silvery baroque-style (“crinkly”) pearl – but its weight matches precisely.

These pearl finds caused a “pearl rush” or “pearl mania” in the later half of the 1800s which began to deplete mussel populations. It got worse between 1890 and 1930, because freshwater mussel shells – specifically the mother-of-pearl interiors – became the most popular and common source of buttons in North America, prized for their carve-ability and opalescent sheen.

It was only until the advent of commercial plastics that the button industry collapsed, and a hundred years later, mussel populations have built back up once more. Freshwater mussels once again represent the largest portion of biomass in many waterways throughout the State, and are pretty much off the radar of the average New Jerseyian.

So, should you drop whatever you’re doing and run out to the nearest stream or river to look for pearls because now it’s “safe”?

Well, no. There are still serious caveats and considerations.

Like I mentioned at the beginning – where are some dozen+ species native to New Jersey, all but three of them are severely endangered, and are protected at either the State or Federal level. The three least concern species are the:

- Eastern Elliptio (Elliptio complanata), the

- Alewife Floater (Utterbackiana implicata, formerly Anodonta implicata), and the

- Eastern Floater (Pyganodon cataracta).

There are also several introduced or invasive species that are “safe” (or “compulsory” to remove in the latter case) which include the

- Paper Pondshell (Utterbackia imbecillis – what a binomial name – it almost looks like it means “say again, idiot?” – however “utterbackia” means “outer-round” or “outer-pearl” and “imbecillis” means “fragile” – an apt description of this species’ ultra-thin shell), the

- Lilliput (Toxolasma parvum – introduced in a few places in South Jersey), the

- Chinese Pond Mussel (Sianodonta woodiana – highly invasive, apparently piggybacking in on tilapia gills), and the

- Giant Floater (Anodonta grandis – a close relation of the Eastern Floater) apparently introduced in the State, whose status has not been assessed.

Everything else is on the “do not touch” list (or rather, catch and release immediately).

Only a small portion of these protections are a holdover from “pearl/button mania” as some species in some places simply evaporated and could not be replaced. The biggest contributing factor, however, is habitat depletion: Dams, serious pollution, and the death or depletion of host fish (some mussel species are very specific about their hosts, and if those disappear, so do the mussels). Invasive species like Asian clams (Corbicula fulminea) are also competing for food and space, too. So, if you’re caught keeping even the shell of one of the protected species (and you can’t prove you’ve collected them from a jurisdiction that they are not protected) you’ll be hit with a serious fine, and have all of your fishing equipment confiscated.

What makes it harder is that some of the endangered species can be confused with the common species, so you’ll need to be familiar enough with these critters in order to tell them apart safely.

What makes it even harder (and ironic) is that most of the State-sponsored identification keys require you to observe internal features of the shell… in other words a dead specimen (so, yes, it’s pretty much, “these are protected so don’t kill them or else, but you can’t tell if it’s protected for certain until after you kill it…” – although if you’ve found an empty shell, these features are convenient to use).

Even if you’re good with your identification, there are limits on harvesting. Since all freshwater mussels are classified as Non-Game Species, you must get a special scientific collection permit which is a separate thing from the normal freshwater fishing license, or the saltwater registry. If you don’t have it, you’re in serious hot water and additional trouble.

So what can one do to appreciate these fascinating critters without trouble? There are two things you can do. First, you can take part in a local Mussel Survey. There is an ongoing effort in the Delaware Estuary. But one can always survey an area unofficially using the Delaware Estuary’s protocol and submit their findings of any endangered mussels (or other endangered animals) directly to the State.

Second, thanks to local muskrat and raccoon populations, collecting the shells is incredibly easy – they tend to leave little piles of them occasionally on the shores. Some of them are rather large and can contain beautiful blister pearls that can be made into jewelry.

Over the course of the next month, I’m going to try and share pictures of my own shell specimens, as well as my progress in several freshwater mussel projects and research I’m fiddling around with, so stick around. It’s bound to be interesting. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve